Why Luis Arévalo is the tuna monarch of the Nikkei

Summary:

A logbook by Sensei Hiroshi Umi.

According to his specialisation, in etymological terms he is a “child of the sun”, which is what nikkei means in my native tongue. The term has over time come to mean this Japanese-Peruvian fusion cuisine, created by Japanese emigrants and their descendants in the South American country sometime in the 1980s, although its roots can be traced back to the late 19th century.

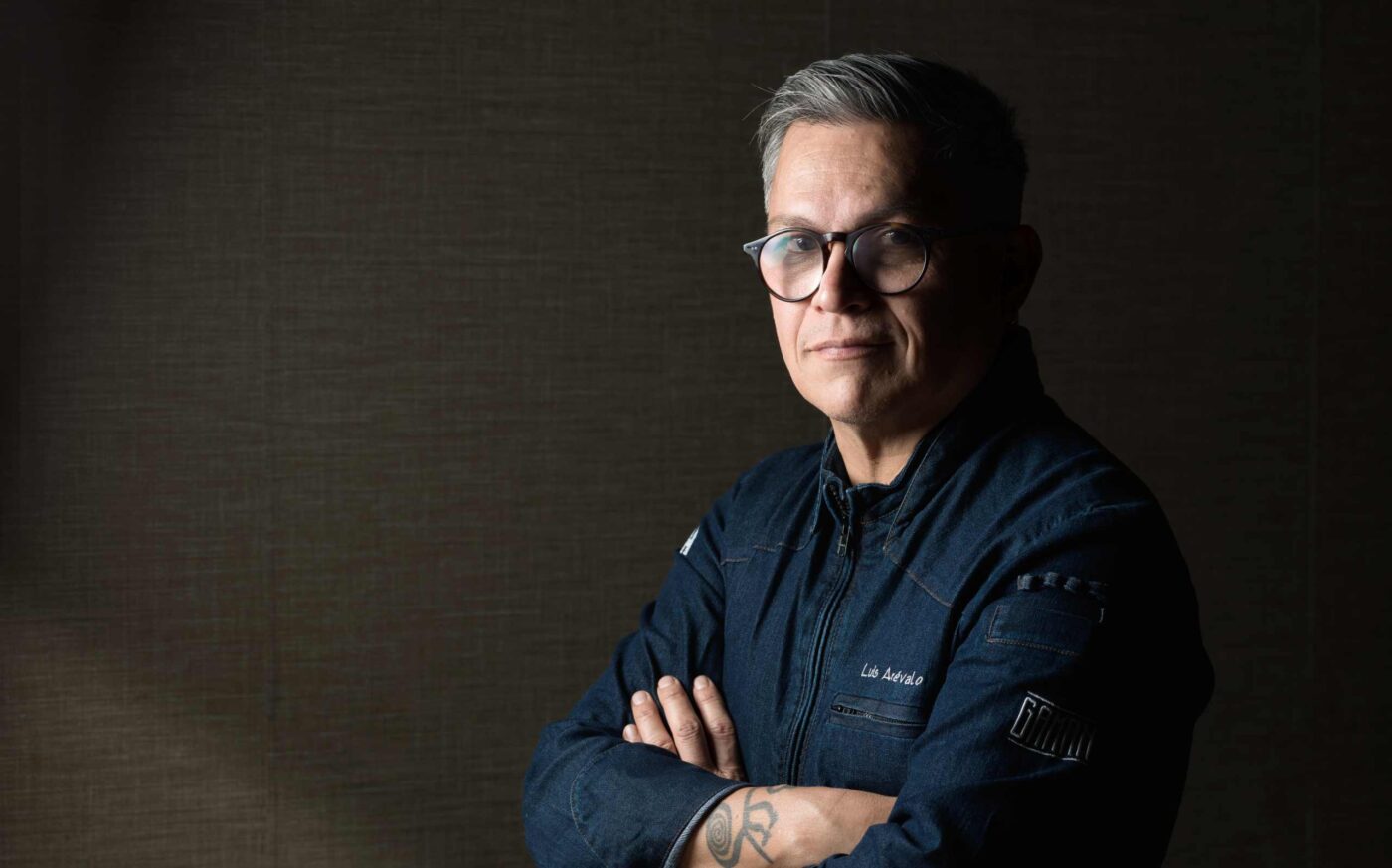

In Spain, no one knows this culinary skill like the pioneer Luis Arévalo, who imbibes and distils the finest of the Orient – above all the cuts of fish, served raw – combined with the methods of his South American homeland, whose cuisine is worthy of addition to the Intangible World Heritage list. We met up with Arévalo at Gaman, his culinary establishment in Madrid (Calle Ferrer del Río, 7). There is an air of moderation, maturity, exultant calm and balanced enthusiasm about him. After a little to-ing and fro-ing, and the typical doubts as to his life and profession, he now admits that he is “really at home in Madrid, although I like to get out and about”.

After more than two decades in Spain, he has built up enough baggage to give him the commercial perspective and personal focus needed to achieve glorious fulfilment. “I feel things are going really well for me right now. Gaman has been a rebirth, resurrection. It means patience, or rather the strength that people now call ‘resilience’. And I also think it combines the maturity of my proposition, my growth. The flavours are much more accomplished now, with the colour scheme and light that have always been my features. I really do believe that I have evolved,” the chef asserts, having previously been a director of photography in his native country before getting involved in the culinary world.

“I made adverts, documentaries… My brother is a film director, and I got caught up in all that with him. I came across cuisine later, at Sushi Ito, in Lima, and above all when I emigrated to Santiago, in Chile, and met Koichi Watanabo. He was my sensei at the Sakura restaurant in the capital of the country, and taught me a great deal. After 6 months by his side he said: ‘You are now ready for sushi.’ And he put me in charge of the sushi bar at the best Japanese restaurant in the whole of Chile,” Arévalo recalls.

From Kabuki Group to Gaman

He ended up in Madrid with all those lessons learned, fascinated by the product being marketed in Spain. And he brought with him a rootsy, researched, deep and questing cuisine. He set to work for four years at the Kabuki Group, the perfect university to polish his technique, before spending time at 19 and 99 Sushi Bar respectively, and then setting up Nikkei 225 as a solo venture. A venue which is still remembered with affection and succulence by numerous patrons, serving as the preliminary to the riotously wonderful Kena. “It was challenging to begin with. I planned on setting up a little tavern, a yakitori, serving a few simple nigiris, a decent sashimi… But it turned into a real happening, and I had to open bigger premises. It was a victim of its own success,” admits the chef, who hails from Iquitos in the untouched Peruvian jungle.

Well equipped with plenitude and balance, Arévalo pursues two different conceptual approaches. One of these, less purist, more chilled out, props up the bar at a venue by the name of Akiro, “which has really taken off, is racing along, with hand rolls and no bookings; I have 6 chefs there and space for 34 covers. Akiro means ‘likeability’, ‘charisma'”; the other narrative is reflected in Gaman, “where I revisit the Nikkei menu, with years of culinary history behind it. In both cases I prioritise the ingredients, such as bluefin tuna with the Fuentes hallmark, which is essential for my cooking,” he mentions.

A feast of bluefin tuna on the menu

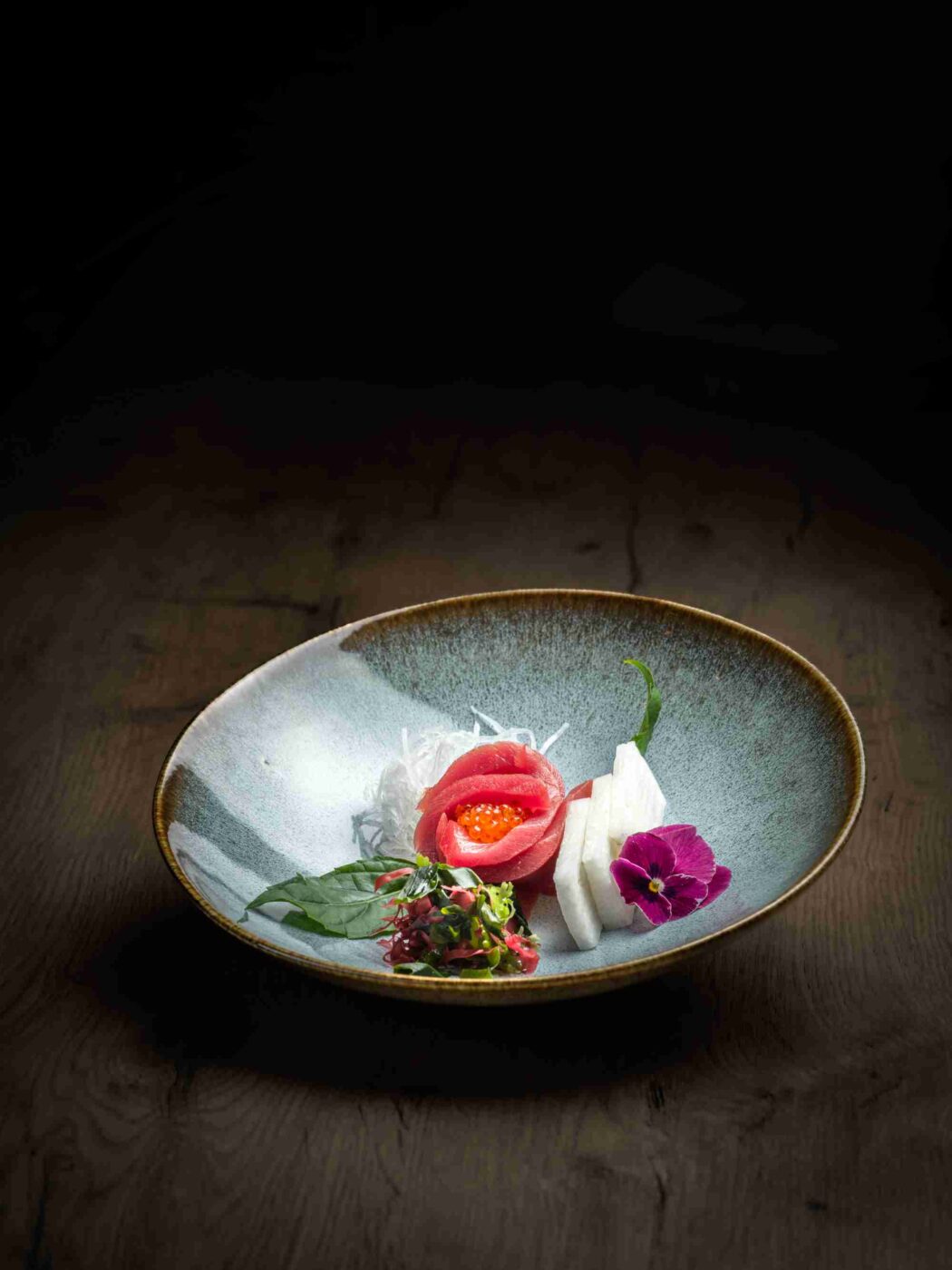

Arévalo splits himself between two concepts, then, with Gaman as the skilful spearhead, with more accomplished dishes, better produced and with more visual appeal than ever, through a sophisticated simplicity. The bluefin tuna sashimi is in the classical style, with a lingering aftertaste (as many as 12 cuts are included on the menu), accompanied by roast daikon and seaweed. “I really like the colours in this, a dish must always captivate your eyes first to deliver the complete culinary experience,” he reflects.

His mastery of the blade and cuts across the grain is amply demonstrated by his usuzukuri with yellow chilli pepper marinade and wasabi, as well as his tuna tartar with tortilla, diced green plantain and chilli and sesame sauce (there is also a guncan version). And there is likewise room for a tiradito made with our titan of the seas, served with cucumber, shredded sweet potato, nori seaweed and a highly distinctive and citric oyster sauce. As well as an outstanding tataki with tiger milk, warm in this case, a ceviche-style creation revealing its origin and method. “I get through 25 kg of bluefin tuna a week at Akiro, and around 5 kg, mostly for nigiris, here at Gaman, although demand is on the increase,” he recounts. The nigiris are served with a virgin soy glaze “which I prepare myself, and then add shijemi mushrooms, escabeche sauce and mashed sweet potato. The kamcha maize powder gives it saltiness. I draw on a subtle, elegant technique, capable of combining salty, spicy, acidic… I remain true to the traditional recipes of my homeland,” he explains.

Gaman takes flight by tracing out a filigree, revealing the dazzling trajectory of a chef who served as a pioneer in Spain by introducing this culinary alliance between Japan and Peru. And he is still adding further flourishes to his logbook: sanguchitos live side-by-side with edamame and chirasi, anticuchos with gyozas, hake sudados with the finest toro topped with foie gras and rocata jam… The sovereign is back. Long live King Nikkei.